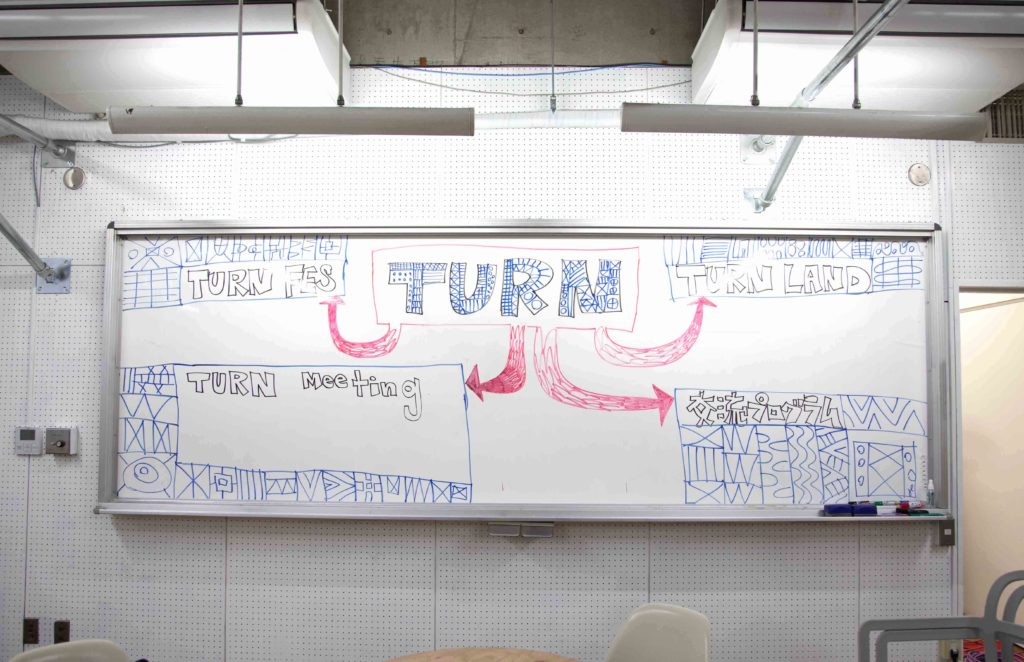

“TURN Meeting” is a series of talks in which a variety of guests join us to discuss the possibilities for interaction and expression generated by each person’s “differences.” TURN Meeting No.11 was held on Saturday, September 19, 2020, the first session to be held online due to the spread of COVID-19.

Under the current climate , the very act of people engaging and interacting with one another at close quarters necessitates a different mindset and behavior than before. This session focused on thinking about different ways to meet, engage and communicate through various methods and tools. Making use of new technology such as online streaming, we provided a platform for people to think about the meaning of communicating with people with different backgrounds.

Our guest was Atsushi Mori, who researches communication methods and support that uses ICT (information and communications technology) for the deafblind community. Born as a person with deafblindness Mori, who has lived his entire life not being able to see or hear, uses a range of communication methods such as tactile sign language to learn about the world around him and engage in dialogue with others. During the session, meeting Mori for the first time,TURN Supervisor Katsuhiko Hibino attempted to exchange his outlook on the world with that of Mori through dialogue and clay modeling.

What lies ahead for exchange and interaction that transcends “distance” in every sense of the word? In this report, we give a snapshot from this day.

■Delivering a number of “languages” online

The emergence of a new virus has presented many challenges to TURN, whose activities revolve around “interaction.” Changes were required in the way we engage with partner facilities, and we had to cancel TURN FES 2020 in summer, a lively event which attracts a large number of participants and visitors. Given the circumstances we have been trialing new responses this year, such as publishing TURN Journal on a quarterly basis rather than biannually as previously. Holding this meeting online was also one response to the situation.

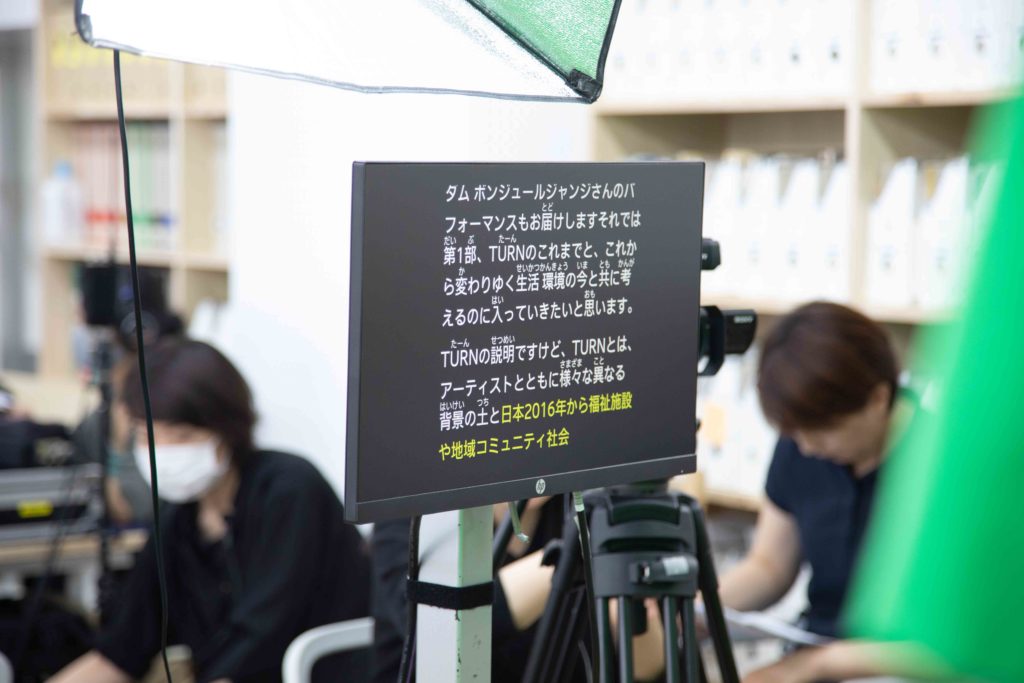

At noon on Saturday, September 19, ROOM 302 at 3331 Arts Chiyoda from where we streamed the event looked different than usual. The usually deserted space was taken up by technical staff, cameras and other equipment, cables etc. There was a feeling of tension in the air in the final stages before rehearsal, ahead of the actual event due to start from 14:00.

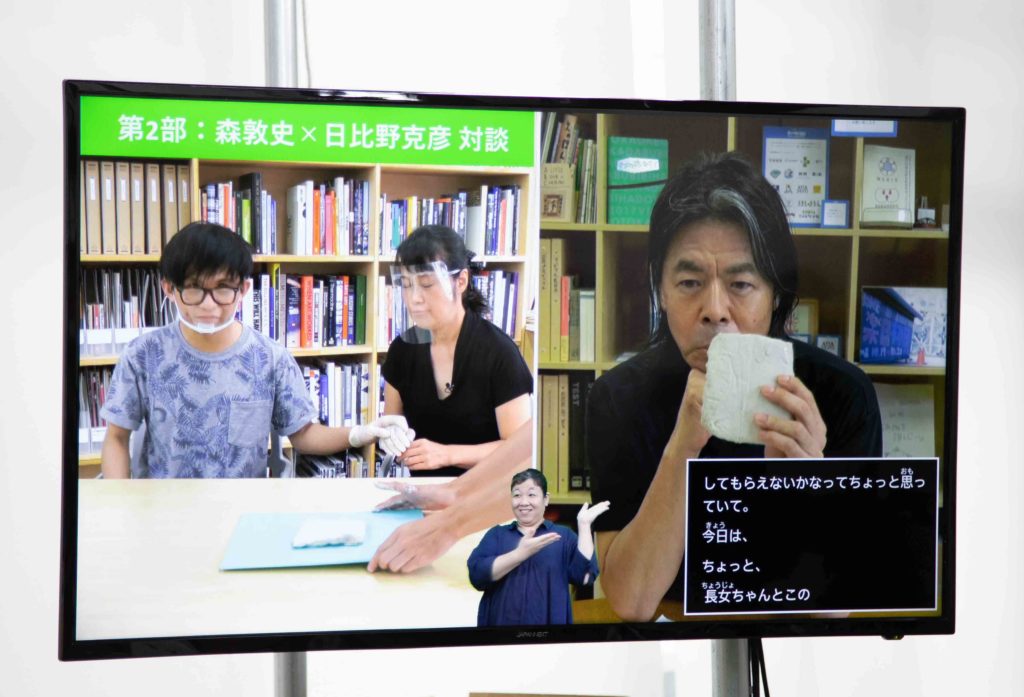

What makes the online version of a TURN Meeting different to many other streamed events is the number of different “languages” we used to reach our diverse participants and viewers.

Looking around the room, moderator Laila Cassim was sitting in front, guest Atsushi Mori and two tactile sign language interpreters were by the back window, next to them was “katsuben” Kotaro Dan providing on-the-spot live narration (audio description) for the event, and by the corridor side were four sign language interpreters. For this Meeting, sign language interpreting entailed a hearing interpreter converting the performer/speaker’s words into sign language, and then a deaf “sign language navigator” standing opposite relaying the message into native sign language again, and delivering them on screen. This method emerged from an idea that the interpreters had, based on their feeling that a deaf person’s facial expressions and movements would give a richer nuance to signing and make it easier to convey what the speakers were saying.

In addition, speech during the discussion was displayed real-time as close-caption text on screen.

A variety of “languages” were flying around a single space, fitting onto one screen. TURN Supervisor Hibino took part from a different room in the same building. In order to connect the various unseen threads of communication, a script was prepared, and the flow for the actual event checked during rehearsal. The feeling of tension beforehand was something we had never felt before in previous TURN Meetings.

■Like the excitement of changing classes in school

Finally, the livestream began at 14:00 sharp. In Part 1, Hibino and TURN Project Director Tsukasa Mori talked about the concept behind the word “TURN” and the exhibition “TURN on the EARTH: I Am an Echo of the Earth,” held during the summer of 2020.

“TURN on the EARTH” was an exhibition held at The University Art Museum, Tokyo University of the Arts which introduced works by ten artists involved in the development of TURN’s overseas projects. Each artist’s section was loosely divided by large transparent pieces of fabric, and if you pointed the handheld tablet (given to you when you entered) at the QR codes which accompany each work, text would appear on screen, giving background information to the work and video footage showing scenes from interactive activities, along with an echo-like sound.

Talking about this system, Hibino said “The key point was how to transpose the activities and events at partner facilities from the Interactive Program to an art museum setting. The sounds you can hear in the venue each time you retrieve information using the tablet were designed to turn the visitors themselves into conveyors of information.”

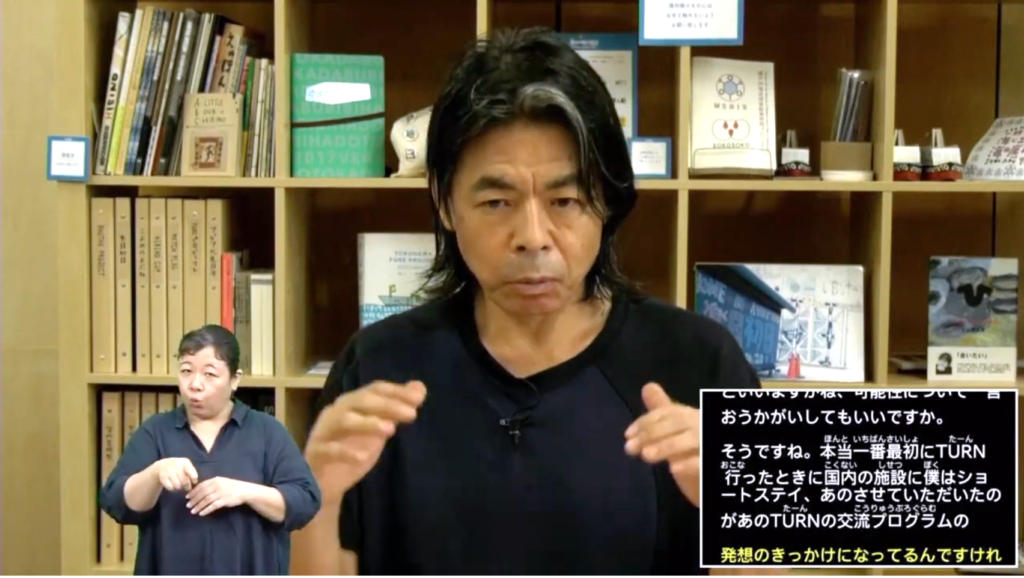

TURN is now expanding overseas, but there was plenty of trial and error involved in the process of arriving at a concept that differs from established frameworks such as what is known as “art brut” or “outsider art.” Tsukasa Mori recalls that major incentive was provided by something Hibino said in passing about “the power that people have from the very beginning.” Hibino says that the background to his words lay in his experience of staying at facilities such as the Mizunoki Museum of Art, affiliated with a residential facility for people with severe learning disabilities, as part of a project that was to be the forerunner of the current format of TURN.

“At first I was unable to communicate with the facility users. But after spending a few days there, I gradually began to see the people for who they really were. When I was shown the place where users make things at the facility, various thoughts came into my mind. What does it mean to draw a picture? What are the differences between people? From then on, I began to think about interaction centered on the elements that form the essence of the individual, regardless of whether they have a disability or not.”

Tsukasa Mori said he thought that the impact Hibino’s experience at the facility had on him was akin to how he himself felt when he first met Atsushi Mori at “TURN FES 5” the previous year. Atsushi Mori, who studied fantasy at Japan Lutheran College and is currently studying various ways to communicate with the deafblind, is also involved in support for younger deafblind children. Atsushi Mori, who attended TURN FES as a participant, was introduced onscreen in photos of him enjoying FES through tactile sign language, and dancing salsa.

Hibino, who was meeting Mori for the first time that day, said he was really looking forward to meeting him. “It was the same when we started TURN and I went to partner facilities. Whenever you go somewhere you don’t know, along with an anxious feeling, wondering what’s going to happen to you, at the same time you feel a sense of excitement. Your outlook on the world expands bit by bit from these feelings. I get the feeling today’s encounter will be like that. Similar to the excitement of joining a new class in school when you’re little.”

■A fun collaborative event with a picture book and audio guide

Between Part 1 and Part 2, a performance by drag queen Madame Bonjour JohnJ lightened the mood. The flamboyantly dressed JohnJ appearing dancing to music, sat down to gave a read-along from picture book It’s OK to Be Different by Todd Parr (published by Little, Brown & Company, Japanese translation by DQSH Tokyo).

This is a picture book which inspires children to celebrate their individuality by looking at the physical characteristics and personalities of a succession of children and animal characters. For example , “It’s OK if you’ve lost a tooth!” To JohnJ’s shouts of “OK!”, people in the room made the OK sign with their fingers saying g “OK!” in response.

What was interesting here was the interaction between JohnJ and “katsuben” Kotaro Dan, who offered barrier-free narration of information to visually impaired audiences on the day. When JohnJ showed a picture of a rabbit and read out, “It’s OK if your ears are big!” Dan said, “The rabbit’s ears are too long to fit on the screen!,” embellishing the pictures with well-timed humor as if he was returning a tennis serve. It was an improvisational and entertaining moment based on collaboration between a picture book reading and an audio guide, going beyond its function as an aid for the visually-impaired.

After reading, JohnJ exclaimed: “Did you know there are 7.7 billion people in the world right now? But there’s only one of you. Isn’t that amazing? Give yourself a hug!” At this the other speakers/performers gave themselves a hug.

Atsushi Mori also seemed to be enjoying the performance, raising his arm to communicate an “OK” through tactile sign language, and hugging himself.

■What does “things you haven’t touched” mean for a deafblind person?

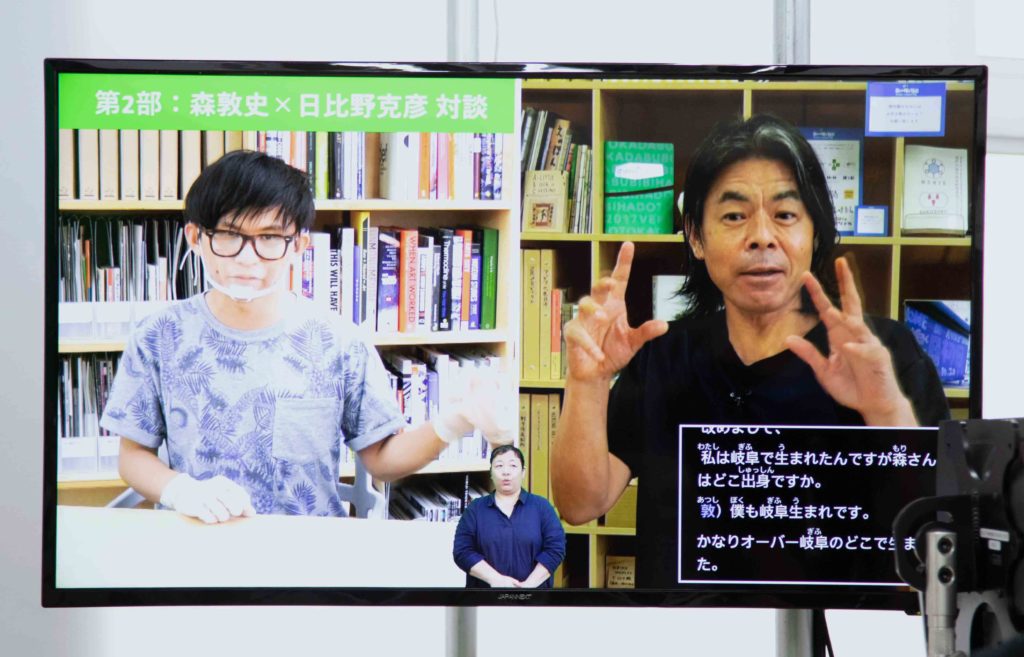

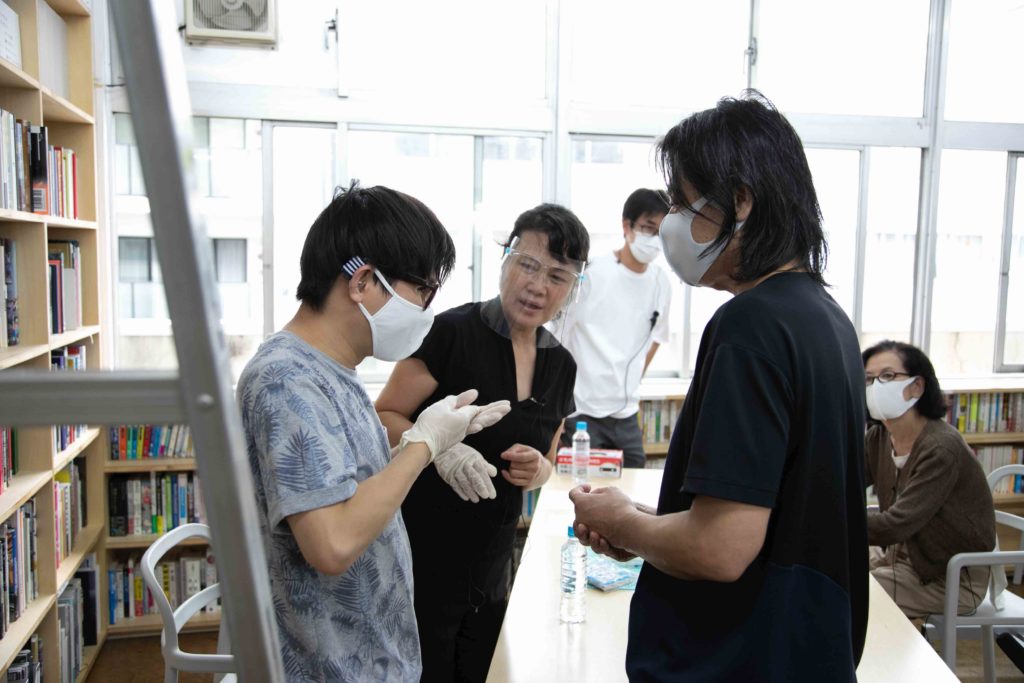

In Part 2, Hibino and guest Atsushi Mori started their talk session.. Mori’s mother tongue is tactile sign language, in which he “reads” the signing provided by movements of the interpreter’s hand by placing his hand on top of the interpreter’s.The dialogue proceeded through the interpreter communicating what Hibino said to Mori, and the interpreter converting Mori’s sign language reply into speech.

First, they both introduced themselves. Hibino said, “I’m from Gifu Prefecture,” to which Mori replied: “I’m from Gifu too.” From the perspective of many, their conversational exchange might have seemed slow, involving very few words. But witnessing communication with someone who is deafblind through tactile sign language for the first time left in awe.

The topic of conversation quickly moved from their hometowns to tactile sign language. When Hibino asked how Mori had learnt tactile sign language, Mori replied:

“Sign language is similar to signs and gestures. For example, the sign language for “eat” also describes the action of eating through hand movement. When I was a child, I learnt simple signs, and from there gradually learned signing. You learn sign language in conjunction with experiences in daily life: you learn the signs for daily actions and things you touch in daily life, for example you learn the sign language for “sleep” if you are going to sleep. People without disabilities learn words that enter through their ears, but I learnt by imitating what people around me said to me in sign language.”

The act of touch carries huge weight in Mori’s perception of the world. When asked if he felt any limitations or inconvenience in communication via tactile sign language, he said “Understanding things I haven’t touched and abstract concepts.” He said that the concepts of “God” and “the world” had also been difficult for him to grasp but he gradually came to understand them through talking to many people. He went on to say that he did however find it difficult to distinguish between “truth” and “lie.” At university, Mori conducted research on the process by which a deafblind person understands fantasy. Unlike non-disabled people, who know empirically what does and doesn’t exist in the world of fantasy through vision, the deafblind “will take a fairy story as being true” he said.

What left an impression on me was when Hibino asked, “So things you haven’t touched or can’t understand don’t exist for you?” and Mori’s assertive reply was, “Well, in a sense I think things you haven’t touched or experienced yourself represent a state of nothingness for a deafblind person.” Hibino seemed very interested in this reply. It interested him because when drawing a picture, he sometimes relies on a vague image of the sort of thing he wants to draw, that is, a sense of something that does not exist in the world yet and cannot be touched.

Hibino then said, “I feel Mori-san that you are also probably capable of turning something you haven’t touched into something you can.”

Mori replied: “It’s difficult, but I might be able to visualize something like a fairytale from something that I have touched. I think it’s possible to imagine and create things in the way I want from what I have experienced or touched.”

■The things a person feels support their existence

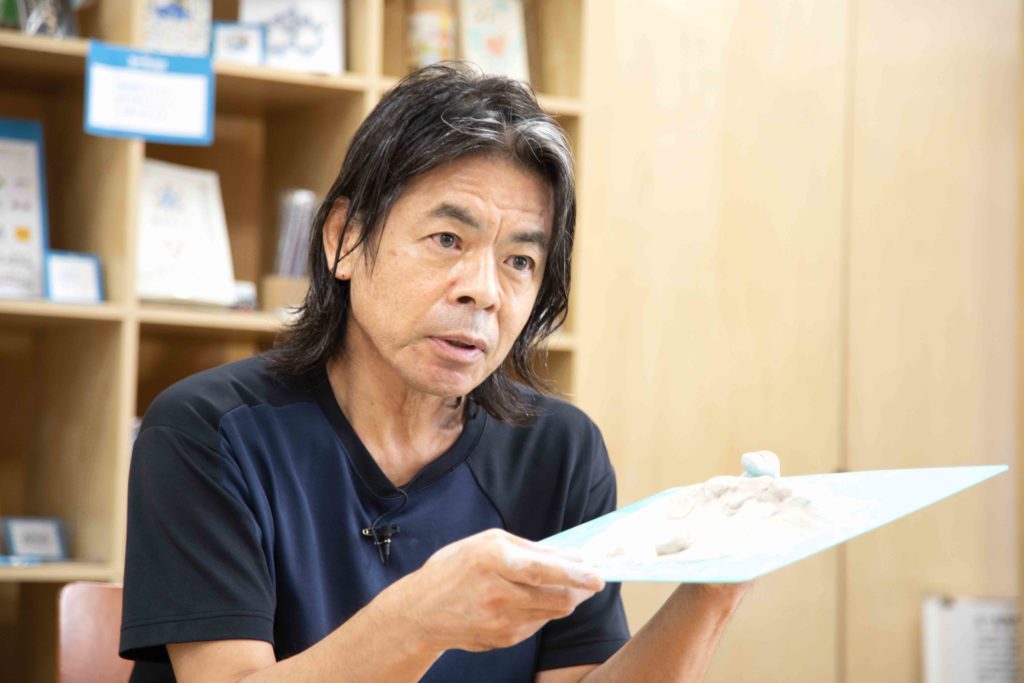

After this exchange, in the latter half of their discussion, Hibino suggested that they try and combine their visions of the untouched and unknown into a concrete form, and some time was given to them to experiment with some modeling clay. The motif was what they both had in common, Gifu. They decided to make something suggestive of “hometowns.”

In their separate locations, the two silently worked their hands.

Mori first made the clay into a strip, flattened the part in front of him, and then placed pulled-off pieces of clay on it. Hibino, on the other hand, created a shape while looking into space instead of at his hands. It took about 5 minutes for both works to be completed.

Mori had made a flat paint palette-like object with five clay balls on it, and Hibino had created something like a large ring.

When asked what their objects represented, Mori replied: “I had in mind the ocean. Gifu has no ocean, so I remember when I was little I went to the beach in another prefecture. The small bits are shells or boats. My representation of the ocean is all based on things I have touched.” He explained the slight incline on the surface of his clay object as being because “the beach is on a slight incline.” It was something he made in a short time, but in it he had perfectly managed to express the image of the world that he felt through his sense of touch.

Hibino on the other hand said he had a concrete scene in mind but rather than replicate that, he shaped it into something like the air that flowed through it. It was a powerful contrast, with the seeing Hibino depicting an abstract image, and the deafblind Mori giving a concrete representation of the ocean and the coast.

Afterwards, they swapped creations at Hibino’s suggestion that they feel the objects each had created. With a slight grin, Mori handled Hibino’s clay object and said, “At first I thought it was a pond, but it’s something different. I have no idea what he wanted to represent “(here he smiled wryly). “But the desire to represent something came across.” Hearing this Hibino applauded. “I’m sure of what I feel, but conveying that to others is a different story. I think the existence and value of a person lies in the very fact of sensing they want to communicate something. It’s enough if you can tell that somebody wants to convey something,” he said.

What was striking to Hibino was the fact that Mori had replicated the ocean. For a past project, Hibino had laid down a 100m-long roll of paper stretching from the ocean to the beach and painted on it. What he found difficult was trying to work with the changing sensations caused by the rising and falling of the waves. “The shore is a place where various things are accessed, where they mix, and where they TURN. In the landscape of the shoreline waves created by Mori, his experience of touching so many things and communicating with diverse people through tactile sign language really came through,” he said.

Mori said his representation of the ocean was based on the image he had of it as vast, through hearing stories of ships, and his own experience of his feet not touching the ocean bottom. At the end, Hibino invited Mori to go diving with him sometime, to which Mori replied: “If I can feel for myself the depth of the ocean and what the seabed is like, I might be able to expand my image of the sea. I’d then like to see if I can represent it again in other ways using modeling clay and.” Hibino responded, “Let’s meet in the water next time!” to which their talk session came to a close.

■Expanding forms of communication

Even after the livestream (event) had ended, Mori and Hibino were still talking about the ocean. Apparently, Mori has been to the beach in Ishikawa and Toyama Prefecture with his family. When he heard this Hibino mentioned he was doing a project himself around the Seto Inland Sea and suggested that was where they should go diving together, to which Mori replied, “Absolutely.” You could see the existence of the ocean emerging as a place in common, bearing new possibilities for each of them.

What kind of thoughts followed their first encounter and communication?

Mori says what he felt was “the difficulty of expressing abstract concepts like fantasy, and things I haven’t personally had the experience of touching.” On the other hand, during the discussion he talked about this difficulty as not only an issue for him but as something that presented difficulties for the deafblind children he works with, making some comments from an educational perspective about new ways forward to tackle this issue. Mori was asked what kind of challenges he wanted to take on going forward as a result of this discussion. He replied: “How can we make deafblind children understand fantasy and abstract things? This discussion has given me the opportunity to start thinking about this, and has made me think it would be good to have some sort of approach like this in art classes. I want to think about that in future.”

Hibino said he would always remember Mori saying that things he hadn’t touched were non-existent to him. As someone who can see, hear and talk, he said he himself is fascinated by proto-linguistic conceptualizing, and the urge to explore it has become the motivation for his creative work. “I had a presumptuous expectation that deafblind people would be swimming freely around in a preverbal world, but I’ve been told in no uncertain terms that things you haven’t touched mean nothing and don’t exist. But part of me wants to question if that is really true.”

Hibino added, “Maybe it’s just that there are still some parts of us that can’t be reached with just the communication methods we have now.” In the same way Mori wants to convey new sensations to deafblind children, Hibino says he “had a hunch that meeting in the water might open a new circuit within.” It seems that the time they spent in discussion, going back and forth between each of their worlds, has provided the opportunity for Hibino to turn his mind to unknown possibilities.

Incidentally, there was another discussion in the room after the livestream: a review of the event by all the staff involved. It was the first livestream of a TURN Meeting that they had worked on while ensuring maximum accessibility. A lively exchange of opinions ensued regarding the contrivances and ingenuity behind the event, the issues and challenges,the points for improvement, etc.

For example, how would you use sign language to convey JohnJ’s occupation as a drag queen? The technical staff said they had consulted the sign language interpreters in advance and come up with new signs. Barrier-free “Katsuben” voice narrator Dan also suggested adding audio to the standby screen prior to streaming to reassure visually impaired people who couldn’t see what was going on. In addition, somebody voiced the opinion that color-coding the audio guide subtitles on the UD Talk screen would provide sighted people with a visual experience of the entertaining speech-to-text commentary.

Online streaming which took place due to the unexpected circumstances of a pandemic. The ingenuity shown in the process and all the findings will help shape the next interactive event. Holding a TURN Meeting in this new format got many of us thinking about diverse methods of communication as well as about the discussion contents, through the trial and error of those involved as to how to deliver it.

We will announce the next TURN Meeting on our website as soon it is confirmed. So don’t miss it!

Written by Tamaki Sugihara

Photography by Ryuichiro Suzuki