TURN in BIENALSUR Exhibition Opening

2017.9.16

The inaugural International Contemporary Art Biennial of South America (BIENALSUR) opened in 32 cities in 16 countries, centering around Buenos Aires in Argentina.

TURN was invited, and kickstarted its involvement in the project with “TURN in BIENALSUR”. Seven artists working in Japan, Argentina and Peru participated, using traditional techniques and practices to implement the Interactive Program during regular visits to welfare facilities and local communities in South America.

The works resulting from this interactive process will be shown in exhibitions and workshops in Buenos Aires and Lima.

Organizer: National University of Tres de Febrero – BIENALSUR

Production support: Tokyo Metropolitan Government, Arts Council Tokyo (Tokyo Metropolitan Foundation for History and Culture)

■ Buenos Aires, Argentina

Period: Saturday, September 16 – Sunday, October 29, 2017

Venue: MUNTREF Museo de Artes Visuales of National University of Tres de Febrero

Artists: Tomoko Iwata, Daisuke Nagaoka, Alejandra Mizrahi, Iumi Kataoka, Sebastian Camacho Ramirez

■ Lima, Peru

Period: Monday, September 25 — Sunday, October 29, 2017

Venue: Centro Cultural de Bellas Artes

Artists: Yasuaki Igarashi, Henry Ortiz Tapia

【Artists × welfare facilities and local communities × traditional crafts and techniques】

Tomoko Iwata ✕ Caminos Foundation ✕ Origata

Daisuke Nagaoka ✕ C.E.N.T.E.S N°3 ✕ Wagashi

Alejandra Mizrahi ✕ Brincar ✕ Randa

Iumi Kataoka ✕ AlunCo Foundation International ✕ Shibori

Sebastian Camacho Ramirez ✕ C.E.N.T.E.S Nº 1 ✕ Chaquira

Yasuaki Igarashi ✕ Cerrito Azul ✕ Indigo dyeing, Andean textiles

Henry Ortiz Tapia ✕ Educational Institution N °1027 “REPUBLIC OF NICARAGUA” ✕ Shicra

※Please see the “Who” list page for details of artists, welfare facilities and local communities.

【Interactive program details】

―Tomoko Iwata ✕ Caminos Foundation ✕ Orikata

After receiving training in origata in Japan, the artist stayed in Buenos Aires from mid August onwards, making regular visits to the Caminos Foundation day services facility for people with learning disabilities where she conducted the Interactive Program. Through the folding and wrapping of “origata”, Japan’s traditional etiquette-related origami, the artist interacted with facility users and staff members and created works together with them.

*Orikata

Orikata is the traditional Japanese etiquette-related art of folding white Japanese paper to wrap gifts. Orikata is used in religious worship during ceremonial occasions like weddings and funerals, for gift-giving, and for the appropriate matching of furnishings/decorations to the seasons in various rituals (a practice known as “shitsurai”). To give a familiar example, orikata can be seen in the everyday custom of using “noshigami” white wrapping paper squares and “noshibukuro” traditional money envelopes as easy and effective ways to express feelings like gratitude. But in ancient times, these were prestigious and highly sacred ritual accessories used at places of religious worship. This is why orikata begins with purification of the self and the area where the paper-folding is to be done. The order of folding and the direction of the angles are also set according to the principles of good and bad luck. Purity and solicitude towards the gift recipient are also embodied in the folding movements.

In addition, the word “orikata” shares its origins with origami as meaning “prayer”. Both are said to have came about as “yorishiro” (objects capable of attracting kami gods) in ancient kami worship, before finally transforming into various beautiful forms expressing thanks for cooperation and support. Another feature of orikata is that you can tell what is inside, and the shape of the folds changes depending on the contents. “Kaishiki”, the paper or leaf placed under religious offerings, is also a form of orikata.

―Daisuke Nagaoka ✕ C.E.N.T.E.S N°3 × Wagashi

After receiving training in wagashi in Japan, the artist stayed in Buenos Aires from mid August onwards, making regular visits to the C.E.N.T.E.S N°3 public special needs school for children aged 3 to 12 with mainly developmental disorders where he conducted the Interactive Program. Together with children attending the school and staff members, the artist underwent the process of making and eating traditional Japanese wagashi sweets.

*Wagashi

Wagashi are traditional Japanese sweets with a unique evolution. Compared to Western sweets, there is little use of oil and fat, spices and dairy products: many wagashi have as their principle raw ingredients grains such as rice and wheat, pulses such as adzuki and soybean, and kanten (agar) made of seaweeds like tengusa (a red algae) that have been boiled, freeze-dried and dehydrated. Wagashi are usually taken with Japanese tea, and as well as being familiar as everyday sweets to go with tea, wagashi are also closely linked to the Japanese tradition of the tea ceremony. Wagashi are also served at annual events, and celebratory or consolatory occasions. Another major characteristic of wagashi is a close relationship to the four seasons: the sweets incorporate the feelings and personality of the sweets maker in order to convey a sense of the arrival of the different seasons through shapes, colors and naming. Wagashi culture is considered to have seen a leap in development from the Edo period onwards, when people were able to devote themselves to making sweets in the peace that followed a long war-torn period. Many wagashi eaten today including the most innovative and sophisticated types have their origins in the Edo period.

―Alejandra Mizrahi ✕ Brincar ✕ Randa

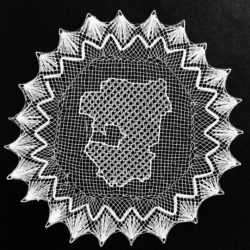

From mid July onwards the artist made regular visits to art classes for autistic children at the Brincar Foundation, where she conducted the Interactive Program. Through the threading, knotting and stitching of “Randa” traditional Argentinian knotted lacework, the artist interacted with children and staff members and created works together with them.

*Randa

Randa is a textile and type of lacework in which knots and fibers are compressed to make mesh of various sizes. In Europe, Randa became a generic word in the field of lace products from the 15th century onwards.

It is a handicraft now practiced almost exclusively in the Tucumán Province of Argentina, especially in the town of Monteros. El Cercado is a village community in Monteros, home to many randa lace-making craftswomen. The lace made in Monteros is completely unique, with the craftswomen using their imagination to sew special names into the embroidery. Randa is said to have developed from the colonial period onwards, beginning with the establishment of Tucumán’s first city Ibatín in 1565. Spanish women who settled here are thought to have introduced the skills of needlepoint lace handicraft and orally passed them on to their descendents. There are about 40 lace-making craftswomen currently engaged in this handicraft.

―Iumi Kataoka ✕ AlunCo Foundation International ✕ Shibori

After receiving training in “Arimatsu shibori” in Japan, the artist made regular visits to the rehabilitation center AlunCo Foundation International where she conducted the Interactive Program. Together with facility users and staff members, the artist created works using the Japanese “shibori” process.

*Shibori

“Shibori” is the Japanese tie-dyeing technique of creating patterns on cloth by binding, stitching, folding, twisting and compressing it before applying dye. The oldest example of cloth-dyeing using this technique dates back to the 8th century. At that time the most commonly-used dye was indigo. Major shibori techniques include “arashi”, “kumo” and “itajime”.

Up until the 20th century, many fabrics and dyes had yet to reach Japan: the main fabrics available were silk and flax, and later on cotton.

In the words of indigo shibori master Motohiko Katano:

“Japanese shibori artisans don’t try to exceed the limits of the materials; they work together with the materials. There will always be unforeseeable factors. In the shibori process, none of the uncertainties inherent in the shaping of the cloth are within human control. It’s the same as a potter burning firewood in a kiln to fire pottery. Even if all the technical conditions are met, what happens in the kiln might be successful, or it might end in failure. Chance and accident have a similarly big influence on the shibori process, and occasionally work a special magic. ”

―Sebastian Camacho Ramirez ✕ C.E.N.T.E.S Nº 1 ✕ Chaquira

The artist made regular visits to C.E.N.T.E.S Nº 1 public special needs school for children with developmental disorders aged 3 to 12 where he conducted the Interactive Program. The artist used the traditional colombian craft of “Chaquira” in his interactions and the works he produced.

*Chaquira

The “Chaquira” technique of decorating textiles with beads developed all over Colombia, making it tricky to explore its roots. In fact you can also find craft items made using the same technique in other areas of South America, but for this project we concentrated on the chaquira of the Kamëntsá indigenous community in southern Colombia.

One characteristic of Kamëntsá handicraft is that items were designed to act as personal talismans to protect the owner and as a result incorporate elements that convey strength and weakness. This handicraft is also the product of shamanistic rituals using Yagé (Ayahuasca) a traditional potion made from a type of vine. For the Kamëntsá people, Yagé is a medium for communication with the spirit world: it is thought that it can waken the consciousness, expand knowledge of the world and above all purify your spirit, mind and body.

―Yasuaki Igarashi ✕ Cerrito Azul ✕ Indigo dyeing, Andean textiles

The artist stayed in Lima, Peru from early August onwards, making regular visits to the Cerrito Azul day center for children and adults with developmental disorders like autism and learning disabilities, where he conducted the Interactive Program. The artist created works using Japanese indigo-dyed yarn and alpaca wool.

*Indigo dyeing

The raw materials for indigo dyeing are a variety of plants containing the indigo pigment. Indigo has always grown wild throughout the world, and since ancient times has been prized as an effective medicinal plant with many uses. In Japan, dyer’s knotweed leaves are harvested, soaked in water and allowed to ferment and turn into “sukumo”, a moldy leaf preparation from which the indigo is extracted. The repeated process of “dipping” and sun-drying ensures that this unique Japanese technology not only produces a vivid indigo color but the dye itself increases the durability of the fabric and the fibers of the yarn or thread. For this project, Yasuaki Igarashi used cotton thread dyed as part of the Interactive Program at Atelier La Mano, conducted there since 2015.

*Andean textiles

Prior to conquest by Spain in the 16th century, Andean civilization flourished in what is now Peru, Ecuador, western Bolivia, the Pacific coast of Chile’s northernmost part and the inland areas of its Andes mountain range. It is said the Andean civilization rivaled that of ancient Egypt, China and Mesopotamia. The textile tradition cultivated by the ancient Andeans is said to have originated some 7,000 or even 10,000 years ago. Their exquisite textiles used cotton, or wool from alpacas and other highland camelids, and were colored with natural dyes. At the loom weaving stage of one of the various processes, two women weave opposite each other, with one end of the warp secured to posts or a tree, while the other end has a strap that goes around the back of the weavers’ waists.

―Henry Ortiz Tapia ✕ Educational Institution N °1027 “REPUBLIC OF NICARAGUA” ✕ Shicra

The artist conducted a program of interaction with the children of elementary school REPUBLIC OF NICARAGUA, situated in an area where poverty, violence and crime are rife. Using shicra bag-making technology practiced in Peru since ancient times, the children, Henry Ortiz Tapia and art school students produced works together.

*Shicra

Shicra, a tradition going back about 5,000 years, means “woven bag” in the indigenous Quechua language. Shicra bags are made of reeds or grasses and based on a crocheting technique called shicra weaving.

In Peru, Shicra bags have been discovered at the site of ancient ruins like Caral and Vichama. We now know that ancient shicra bags were used in construction as part of building foundations, and that making the bags has always been a collaborative effort. In the pre-ceramic era, shicra bags were used to hold organic matter and waste.

The shicra mesh, made with knots and needles, had a wide range of applications. As bags or netting it was used for fishing and harvesting/ gathering, and it was also used as decorative wrapping for corpses to be mummified. Shicra, a tradition of knowledge and technique spanning centuries and unique to the coastal regions of Peru, is these days made as a craft product at Wayra in Lima. Its use may have changed since ancient times, and it may be at risk of disappearing altogether, but shicra production continues on a modest scale.