Talk series TURN Meeting is part of the TURN, which generates artistic expression from encounters that transcend differences. TURN Meeting No. 15, the last in the Meeting series, was held on Monday, December 13 2021 at the Auditorium, Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum. The meeting was first held in 2017 and has been streamed online since the outbreak of the COVID-19.

This milestone event for TURN, which began its activities in 2015, was titled “TURN Now and from Hereon.” Speaking in the first half (Part 1) were artists and partner facility staff members who have been involved in TURN to date, and in the second half (Part 2), Supervisor Katsuhiko Hibino and others. The speakers looked back on thoughts and ideas generated through TURN activities. Between discussions, there was a performance of “TURN NOTES” composed by Akashi Ikawa.

What was the significance of TURN from the individual standpoints of the artists who interacted with the facilities, and the facility staff members who hosted the artists?

Starting from the idea of taking a fresh look at the “Exploring People’s Innate Capabilities,” which has been ascertained from seven years of TURN, a project which also provided an opportunity to re-examine the existing framework of “art”? Here we report on the day’s proceedings.

■ “We don’t really get it but let’s give it a go”

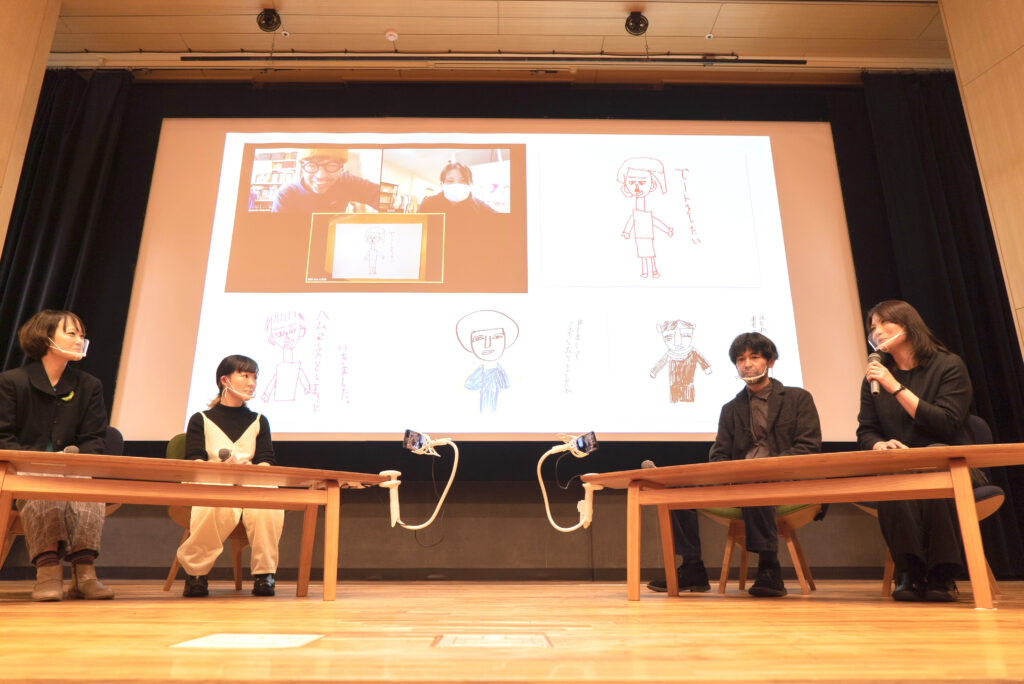

TURN Meeting events have been streamed online from TURN Meeting No. 11 onwards due to the pandemic. This event, taking place in a real-world environment for the first time in a while, started in a somewhat special atmosphere as it was also the last ever session.

Part 1 entitled “Insights and realizations from TURN interactions – Towards a diverse society” featured three pairs of speakers comprising artists and staff from organizations who have been involved in TURN activities. Together with moderators Kanako Iwanaka from nonprofit organization Art’s Embrace and Maria Hata from Arts Council Tokyo, speakers discussed the thoughts and ideas arising from their experience of TURN. The pairing of artists and organization / facility staff was not of people who normally collaborated as partners on the Interactive Program, but instead was a combination of people engaged in different TURN projects, so that the event would offer a new encounter for all.

Session 1 featured artist Daisuke Nagaoka and Noriko Takada, a staff member from Itabashi-ku Komone Fukushien (welfare facility). Their discussion gave a sense of their perspectives in terms of how they had dealt with the confusion that occurs and the “distance” felt when an artist engages with a welfare facility and conversely, when a welfare facility takes in an artist.

For example, in recent years Nagaoka has interacted with facility users at Heartpia Harajuku through portrait-drawing. Nagaoka talked about the beginnings of this activity. He said that one time when he went out into the neighborhood for a walk with a facility user, the facility user didn’t get a response from passersby to his “hello.” Nagaoka said he “learned something very important” when faced with the sight of the facility user continuing to say hello to passersby, even though they didn’t receive a single reply. “If local people don’t want to say hello back, I’m fine with that, but maybe it was a case of them not knowing how to engage. So, I thought that gradually encountering each other through a portrait-drawing activity in front of the facility would encourage mutual understanding,” said Nagaoka, explaining the motive behind the activity.

Meanwhile, for Takada on the facility staff side, it wasn’t easy for the facility to accommodate and assimilate a project like TURN dealing with art – something she “doesn’t really understand” – when their days were already so busy. But looking back, she thinks that the reason they were able to carry on with TURN Interactive Program activities despite the situation was because the facility manager and staff had the attitude of “we don’t really get it but let’s give it a go.” She added, “It’s certainly difficult to put the TURN experience into words, but it was just a question of deciding to give it a whirl. A major factor in this was the positive way everyone approached it.” Recently, she said, the goals that facility users set for themselves at the beginning of each year have included wanting to “do their best in TURN activities,” something which is apparently generating a facility-wide feeling of wanting to carry on with TURN.

Listening to what Takada had to say, Nagaoka says he could relate to the difficulty of explaining TURN to outsiders. Nevertheless, Nagaoka says he is attempting to share the TURN experience by inviting friends as models for a portrait-drawing project he has recently been conducting online. Explaining the reason for this Nagaoka said: “I realized I was now able to put TURN across in terms of its fun aspect for me. The project might end at some point, but we’ll always have good memories. I felt it was important to share the things and relationships that are important to me, so that other people remember as well.” It seems that for the people involved, the TURN project was also a time to chew over the things they didn’t understand and the distance they felt, and share this with others.

■ The presence of artists brought a heightened sense of self-affirmation

The next session featured artist Sunao Maruyama and Kimagure Yaoya Dandan owner Hiroko Kondo.

What these two guests have in common is that they have both carried out a variety of activities with children. In 2019 Maruyama began Interactive Program activities with the Nepalese government-endorsed Everest International School, Japan in the Asagaya district of Tokyo. Meanwhile Kondo’s “Dandan” is credited with being the first to start the Kodomo Shokudo or “children’s café” movement supplying hot meals to children in the community, and she has organized TURN projects with Nagaoka and other artists including “Otona Zukan,” in which children listen to a talk by guest grown-ups of the sort they would not normally come across in their daily lives. From the conversation between the two, we got a glimpse of the way the presence of an artist has positively affected the children’s environment.

Maruyama said when she first visited Everest, she was surprised that there was no time allotted to music and art in Nepalese schools. In addition, when she went to Everest’s kindergarten to observe an art session, she found that all the children drew similar pictures, making it difficult for her to feel their individuality.

“But the children themselves were full of beans,” says Maruyama. So in order to encourage that raw energy to come out as expression in their pictures, she set aside time for getting them to fold and cut paper and then draw a picture or story based on the resulting random shapes of paper. In a sense, you could say this was a mechanism for them to re-examine the fixed framework they constantly had inside their minds and which led them to think “I should do this,” “I shouldn’t do any more than this,” etc.

In the same way, Kondo’s motive for starting the “Otona Zukan” project with Nagaoka and other artists was partly due to her thinking, “surely there are more possibilities than this” when she saw some school material concerning children’s futures. The material contained the stereotypical image of adult life and work usually shown to children. In contrast, Kondo says, “I wanted them to know that there were more things to do and be as an adult than achieve financial success. I didn’t want to show them only a limited number of possibilities.”

For Kondo, the presence of the artists she collaborated with on TURN seems to have expanded the normal framework. “Having an artist there allowed us to take on challenges that we couldn’t manage by ourselves. It was great that the children were able to experience something different, and being able to connect with other facilities as a result,” Kondo reflected.

Aside from TURN, Maruyama has also conducted a similar art-based project at Nagano Children’s Hospital. She was asked to brighten up the hospital, with many patients with severe disabilities. She designed hospital wards to make children feel like they had entered the world of picture books, for example sticking mirrors in the shape of clouds to the ceiling for children when they were being moved around in beds, or attaching toys to the walls to be enjoyed at a child’s-eye level. “Like Takada-san said before about not understanding but deciding to give it a try, I now value what came out of that project, and the act of creating things with the people there,” says Murayama. You might say this project also deviates from a conventional, fixed approach to environments for children.

What was very interesting at the end of this session was Kondo saying that a sense of self-affirmation had been brought out in the children through their experience of TURN. It would be something like the sense of release and freedom you feel when your unconscious attitude towards the world is shaken up. Maybe TURN has created many such moments.

■ Unpredictability without purpose is the attraction of engaging with art

The pairing for Session 3 was artist Katsuya Ise and Katsunori Shinzawa, the director of Harmony, an employment support facility in Setagaya. A TURN participant since 2017, Ise has conducted interactive projects at the Suginami-ku day service center for elderly people, Nishiogi Fureai no Ie (called Momosan Fureai no Ie until June 2021). Shinzawa has worked with TURN artists since 2015. Their conversation was truly uninhibited and developed in some unforeseen directions!

Actually, this TURN Meeting had felt a little tense up to this point. As if to change the mood completely, from the beginning Ise talked enthusiastically about the outsider folk punk band Love Ero Peace comprising Shinzawa and some Harmony members (users), telling Shinzawa he is a big fan. This is quite a wild band, with the vocalist whizzing around in an electric wheelchair, other band members performing on reclining wheelchairs lying down, people turning up the volume of band members’ amps without permission, etc. Shinzawa says, “We’re very broad-minded, so it doesn’t matter who comes or what happens.” Ise describes Shinzawa and Harmony activities as “punk.”

Then Ise and Shinzawa suddenly invited Harmony members poet Kotaro Masuyama and Masami Kinbara, who came to the meeting as guests, to get up and say something. Everyone was highly amused by what Kinbara said about the “Mito Komon Murder Site Inspection Tour” based on his personal experience of delusions and which he conducted as part of the TURN LAND project “Kamimachi Harmony Land.” The sight of the two Harmony members so naturally and nonchalantly getting up to speak seemed to substantiate Masuyama’s remark: “Harmony is a place where I can feel safe and secure.”

Ise says that at the beginning he engaged in the project from an “oblique” angle without really understanding what TURN was about. But looking back and reflecting on his TURN activities now, he says that “maybe the activities influenced to raise staff motivation a little, or to disrupt the place as a stranger and open something up towards the outside.” I feel like Ise demonstrated this artist-like behavior to the full at this TURN Meeting, too.

What was also interesting was Ise saying “In the sense that artists are also often said not to be understood by society, this might be something they share with people with disabilities.” Listening to this, Shinzawa said that there was a sense of what “ought” to be done in the welfare industry, but he wanted to overturn the “proper” way of doing things at Harmony, and he had expectations of the artists in that respect. “Lots of people come to the facility with a purpose, but I’m tired of that kind of people. Encounters with the important people in your life happen mostly by chance, and you lose that opportunity if you bring a sense of purpose to it. It’s the unpredictability of artists that broadens our horizons.”

On the other hand, it was Shinzawa who had the harshest words to say today about TURN. He pointed out the inconvenient aspects of events under TURN LAND, a program in which TURN activities are open to public participation. Shinzawa articulated his thoughts with a view to the future of TURN when he said, “For TURN LAND, the dates are sometimes set in advance, so sometimes I got drawn into the trap of becoming like a child eager to do things properly, arranging and organizing the events for each year. Setting a minimum number of participants; having preconceptions and fixed ideas about the form interactive activities will take; taking a cheery group photo at the end; safety management that seems excessive; I would like to share with everyone involved in TURN the things that have caused us (the facilities) my inconvenience.” How to take these words is left to the individual artists and staff members involved.

■ A fascinating performance of TURN words with sign language

After hearing from the three pairs of speakers, the work “TURN NOTES” was performed during the interval of the second half of the talk session. Text from “TURN NOTE,” an annual printed booklet of off-the-cuff spoken and written words collected from TURN activities, was set to music by Akashi Ikawa, and performed with singing and readings by baritone Shuntaro Tanaka and vocalist Satomi Watanabe.

* You can see “TURN NOTES” from “TURN FES 6: Online Program” here

The performance began with TURN Supervisor Katsuhiko Hibino’s words “TURN as a connecting word” from TURN Meeting No. 4 in 2018, here recited over music one character/one note at a time. This was followed by words from various people including artists, sign language interpreters, people with disabilities and more. The audience followed the performance with a script given out prior to the performance.

Ikawa said he felt that the words in TURN NOTE were “not only gentle, but also sometimes piercing and powerful.” Hearing these words again spoken out loud, there was a sense that the people involved in TURN had made comments that were not easy to digest, but which felt real.

In addition, the presence of Yuko Setoguchi, who handled sign language interpreting for the performance, was every bit as strong as the two singers. Setoguchi’s movements, which communicated performance content with not only her hands but also gestures using her whole body and facial expressions, were nothing short of the third performer. At the same time, in her well-prepared sign language expression you got a sense of the accumulated results of TURN Meetings that explored the coexistence of different means of communication such as sign language and subtitles in online streams during the pandemic.

■ The possibilities of TURN lie in thinking about disability through culture

In the second half discussion, Hibino and TURN Project Director Tsukasa Mori looked back on five years of project activities.

Encountering diverse people, getting together, thinking together, opening up their existences. Hibino likened these TURN activities over the years to the way he played as a child. “Even as a child, I thought carefully about who to play with and how to play with them. Why do we feel nervous when we meet strangers? Why do people want to do new things? What we have practiced with TURN is no different.”

The two also had an exchange on the difference between “art” in a general sense and the word “TURN.” Mori verified that TURN developed from Hibino’s words, “Exploring People’s Innate Capabilities from within.” Mori said, “TURN is not what you might call a purely “artsy” project, but it works precisely because it involves the word “TURN.” To this Hibino replied, “I wanted to develop art to the extent that it provided vitality and energy for living. Islands might look separated, but they are connected under the sea. I wanted to think about that bedrock, that foundation.”

A shared feeling by people across cultures and viewpoints was also key when the artists visited Interactive Program partner facilities/organizations in Japan and overseas. Mori witnessed many of these interactive activities. “I could feel the communication skills of the artists,” he remarked. Hibino commented, “Kondo-san was saying that the children’s sense of self-affirmation went up, and I think that’s true. All artists tend to be people interested in various things. I think people at partner facilities sense and enjoy that.”

After that, talk turned to the future. TURN, which reached a milestone this year, is scheduled to continue with activities at Tokyo University of the Arts from next year onwards. When asked what he envisages for the project there, Hibino points out that the traditional form of international exchange program at arts universities had focused on expertise, such as technique-based exchange between pottery artists. For TURN on the other hand, with a mindset based on the “foundation” of humanity he talked about before, it should be possible to have more fundamental exchange with social issues as the common theme, Hibino said. Mori also said he thought leaders of cultural programs and projects in Tokyo may have gained a new perspective through TURN, for example changing how they view sign language interpreters, and he hoped this could be leveraged as TURN’s legacy going forward.

Lastly, the two discussed the possibilities of TURN in their own words. Hibino said that listening to participants today, he felt that one of the attractive things about TURN was its unknown factor. “It’s important to interact while taking on what you try to understand but can’t.” He added, “Art is an unknown. And I think that’s why it attracts people in a society that emphasizes so much on understanding so many things. I would like to continue to make this subject matter, something which changes rapidly and which you can never pin down, my field of activity going forward.”

Meanwhile Mori recalled that when he started TURN, Hibino had said he hoped all sorts of facilities including welfare facilities would become cultural facilities. Mori further highlighted TURN’s significance by touching on the “social model” of disability, which posits that a person’s disability is brought about by societal factors and not from the mind and body of the individual: “I think the possibilities of TURN lie in its ability to consider disability within the diversity that culture represents.”

■ TURN towards the person themselves, going beyond categories

And so, the two-and-a-half hour event ended here. Afterwards, there was feedback from speakers at the venue. It seemed that what speakers commonly felt towards TURN was its perceived interest and empathy for the unknown and un-named, as well as its perspective of seeing people as individuals rather than as the sum of their attributes.

Looking back on TURN’s activities, Hibiya said, “I thought TURN could become a big tree, so to speak, after five years or so of activity. But what we were aiming for wasn’t something quite so superficial. But today I got the definite feeling that our vague attempts have taken root and grown. Those roots ought to be the foundation for our individual activities in future.”

Mori responded by summing up TURN from a bird’s-eye perspective. Whereas modern “art” has become more and more fragmented, what he sees beyond TURN, as a project aiming for something more fundamental, is an “arts and crafts-centric” world engaging the vitality of people able to encounter, observe and envisage something. “Nagaoka’s portraits are a case in point,” he says. “You can’t encapsulate this area of art in the phrase “contemporary art” but you can within the framework of TURN. I think the fact we have had a hand in the societal positioning of “art” in this way is a major achievement for TURN.”

An approach that doesn’t place too much importance on existing “art” is something Laila Cassim, MC for the TURN Meeting, can relate to. Cassim says that with the TURN project, art is not the purpose, only an entry point. “People normally encounter each other through the prism of titles and roles, but you can encounter the unsocialized aspects of one another if you put art in the mix. In TURN interactions too, you meet and engage with people on the level of your respective positions at first, but artists and people at facilities alike gradually become just another person to each other, someone from everyday life. I think TURN has placed importance on this change, rather than on the things created.”

TURN’s perspective on “the individual” could also be inferred in comments by Setoguchi, who has been working as a sign language interpreter within TURN. Setoguchi points out that normally sign language interpreters tend to be treated as nothing more than “informational infrastructure” in many workplace scenarios. “But with TURN, I was seen as an individual human being. Like I was first and foremost a person and being the sign language interpreter was incidental. We’ve talked about self-affirmation, and I was very happy to feel I could be myself.”

I think the thing that changed the most for myself (the writer) during regular coverage of TURN meetings was that the compartmentalizing of “the person with a disability” and “the sign language person” weakened and you got a sense of the world and the culture of the individual, specific person. Surely everyone who has been involved in TURN in some form or another has been through changes like this of their own.

We have come to the end of TURN’s activities for the time being, but as Hibino said, the roots spreading out here like underground streams will no doubt evolve in new and different ways wherever the people involved are. I strongly hope the day will come when we can get together again, bringing our respective experiences.

Witer: Tamaki Sugihara

Photo by: Ryuichiro Suzuki

Related Articles